|

|---|

Thursday, December 29, 2005

The answer isn't quite as obvious as one might think. artificial.dk now has a section about art games, or to put it more correctly - video games made by artists. How is that for a pompous way of promoting entertainment, giving it the special "art" status? Of course, some of the works are actually quite far from what one could call a game see, for instance, in the featured selection art games several works are really "hacked" games, made impossible to play or turning the concept of "game" meaningless. The work might be interesting, but isn't calling it a "game" just a pretensious way of promoting "alternativity"?

On the other hand, many art games seem to be just plain games, i.e. entertainment, under an artsy cover. They get you hooked just the same, and the esthetic aspect seems to vanish in the competitive haze. That's what happened to me with arteroids, a game I linked to some time ago. (I even clearly called it a "game", suggesting I don't quite feel arteroids are as "artsy" as its creator Jim Andrews wishes to see them)

The Intruder by Natalie Bookchin is another case. Here is a narrated story, accompanied by several "games", some of which are playable, others, well, symbolic or rather, playing on the idea of playing. It has a low-fi, underground feel to it that makes it at once appealing and irritating. Appealing, because contrary to some all-too-perfect projects, there is lots of room for us here, for changing focus, for trying to figure out a personal way of going through this. Irritating, because when I played (?) it, several times the game seemed to stop or stall. The limit of my low-fi enthusiasm appears just about here.

Labels: digital

Wednesday, December 28, 2005

There are some works of art that stupid people will never understand because they weren't made for stupid people. And there are a lot of stupid people. Why should anyone assume that any work of art can be reduced to the level of comprehension of a contemporary eight-year-old?- Robert Hughes (from this interview)

Many consider Hughes the best art critic in the world. This is his most famous and witty book about contemporary art:

In the preface, he asks: "What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant garde had in 1890?"

And answers: "Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all, the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants."

The thought is impressive. It inspires to lift one's butt and find those necessary metaphors.

But I have some doubts. The idea that art should "find metaphors", and that they are to be the "necessary metaphors", seems both scary, and distant from a modernist perspective. Conveniently, Hughes gives the example of the Eiffel Tower, which was not, however, your typical artistic enterprize of the time. Of course, today we might see it as such, but putting it as a prototype of a work of art of that era it is a projection of our today's perspective.

Doubt #2: The Van Goghs and Gaugins, and even the futurists, were not quite the "culture". They were clearly the avant garde. And with this noble classification came a marginal social status. Thus, we cannot compare today's culture to yesterday's avant garde. Those are simply different worlds. The question might be - do we still have an avant garde? Well, did the average art lover of the 1890's know what was the true, valuable avant garde (as seen by us today)? Of course, we are not just your average art lovers. We are - us. And so we know.

Does an avant garde still have any sense? Or is art so institutionalized it's impossible to see it as this fresh, new force?

I am deeply convinced that avant gardes still exist, as always, in plural, and as always, difficult to see, maybe not as much for aesthetic, as for political reasons. The avant gardes that have prevailed (that we know) seem to be those that have been taken up by some political/social movement. And those movements are yet to come. Today's social currents pick up yesterday's avant gardes and turn them into what we know - starry starry nights and eiffel towers.

Labels: art world, painting/photo, theory

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

The Polite Umbrella, by Joo Paek, respects people’s personal space in a public area. This shrinkable umbrella enables users to morph its shape like a jellyfish in order to reduce occupied space and to increase user maneuverability.

The user can adjust their umbrella by pulling a handle so that one can protect themselves from harsh winds or bumping into others. The video.

(via)

Labels: design/architecture, funny

A key event in the history of modern performance was the presentation in 1959 of Allan Kaprow's 18 Happenings in 6 Parts at the Reuben Gallery. (...)

Kaprow chose the title "happening" in preference to something like theatre piece or performance because he wanted this activity to be regarded as a spontaneous event; somethink that "just happens to happen." Nevertheless, 18 Happenings, like many such events, was scripted, rehearsed, and carefully controlled. Its real departure from traditional art was not in its spontaneity, but in the sort of material it used and its manner of presentation. In his definition of a happening, Michael Kirby notesthat it is a "purposefully composed form of theatre," but one in which "diverse alogical elements, including non-matrixed performing, are organized in a compartmental structure." "Non-matrixed" contrasts such activity to traditional theatre, where actors perform in a "matrix" provided by a fictional character and surroundings. An act in a happening, like Halprin's "task-oriented" movement, is done without this imaginary setting. In Alter's terms, it seeks the purely performative, removed from the referential. The "compartmental structure" relates to this concept; each individual act within a happening exists for itself, is compartmentalized, and does not contribute to any overall meaning.

- Marvin Carlson

Quoted from:

Labels: performing

Monday, December 26, 2005

Here is some good old-fashioned performance art for your viewing pleasure. It is actually a video-performance, or: performance made jsut for the video, by Hyun-Joo Min. She was born in Corea, and has been living in Germany since 1990.

uncut (1998)

In her work Hyun Joo Min is interested especially in the independent or even autonomous reality of the body which the consciousness in nearly all cases ignores, and which evades the consciousness by its becoming classified to be unimportant and insignificant. - Johannes Meinhardt

Labels: performing

Thursday, December 22, 2005

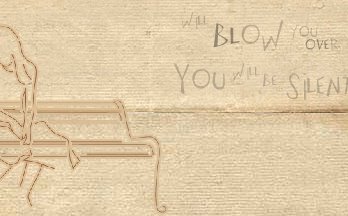

The image above, by Matt Smear, is a Christmas gift for Grijsz. And for anyone who would like to receive it.

Labels: digital, painting/photo

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Yes, it's here. And not just some flaky flowers or christmas trees or your favorite Monet. I'm talkin' all the hypest artists you've heard about (unless you're like me, then most of them you haven't heard about). On your mobile. For the humble price of $1.99 each. Yes, this means it's US only. And yes, the artists are American or Americanish ( e.g. Jorge Naranjo, whose work is above, is of Mexican origin).

This retail art gallery for your cell phone is brought to you by Start Soma, the San Francisco gallery for emerging artists.

(via)

Labels: design/architecture, digital

The Foodloop.

Labels: design/architecture, funny

Monday, December 19, 2005

Simple Version.

Complex Version.

Labels: digital

The smallest Pac Man ever.

The author, Alan Outten, author of the world's smallest website (with many other tiny versions of classic games), has a pretty Christmas card on his site.

And this is my favorite small piece of his.

Labels: digital

Saturday, December 17, 2005

The sad thing is that more and more, we are becoming disconnected with a sense of wonder, of mystery and destiny.Joel-Peter Witkin

It isn't hard to think up something very deep and poetic concerning Witkin: through his imagery, we gain a greater understanding about human difference and tolerance, someone declares. Someone else seems to admire Witkin for nearly the opposite:

His arresting images show us our powerlessness in the face of madness, lust, disease and death.

The thing about Joel-Peter Witkin is that he shows people. And daringly so. The strangest people you have ever seen. In the strangest of poses. In the most surprizing situations. And, although his pictures are full (some say: overfilled) with references to art history, his merit seems to be above all related to this: showing.

Pinheads, dwarfs, giants, hunchbacks, pre-op transsexuals, bearded women, people with tails, horns, wings, reversed hands or feet, anyone born without arms, legs, eyes, breast, genitals, ears, nose, lips. All people with unusually large genitals. All manner of extreme visual perversion. Hermaphrodites and teratoids (alive and dead). Anyone bearing the wounds of Christ.(...) Anyone claiming to be God. God.

Someone states that seeing Witkin's works is like witnessing a brutal car crash. Indeed, we feel voyeuristic, as in, willing to witness obscenity. Being the good art amateurs we are, we look for justifications, just as we might look at the crash "from a distance", inquiring into the reactions of others, or the aesthetic vs. ethical aspects of the scene. We might even go so far as to declare the paintings a cry for tolerance. The question remains: how distant is this cry from the freak-shows history has known time and again? Isn't it just the curiosity of the crippled, the strange, the too-different? Seeing the world without its regular masks?

And if we are just part of a long line of curious onlookers, are we damned? As in, morally condemnable?

Contrary to common belief, monsters weren't only associated with signs of evil events to come, but also, and quite frequently, with signs of devine power. The monster shows were often events where one would discover the many ways of divine creation. (Notice how words like "amazing" and "awesome" also have an ambiguous quality at their origin, but went the other way, becoming generally accepted as positive adjectives).

In this sense, what we see, through Joel-Peter Witkin's eyes, are monsters. They are the marvels.

Meaningful they become. But what is their meaning? And does it not risk turning against those he claims to defend?

One of Witkin's many critics, Cintra Wilson, writes,

The work is beautiful enough to be "real art," but it is still an intellectually camouflaged, carny peep show of the most debased and obvious water. You can put as many flowery wreaths and as much gorgeous photo technique as you want around a dead baby, and it will be art, yes, but it is still a dead baby. It is still a sideshow for the morbidly curious, regardless of how much Witkin may drone on about the deeply religious quality of his work.Then again - Francis Bacon, in that sense, did not evolve, did he?

(...) The artists I respect get more irreverent with age while, at the same time, they humanize; they lighten up, they drop the old mask, they actually start to care about things more and open up a little, laughing about things they used to take to heart as deathly serious. They evolve -- for better or worse.

(the first image is the portrait of Witkin by his wife, tattoo artist Cynthia Witkin)

Also check out one of the most recent of Witkin's albums:

Labels: controversial, painting/photo

Thursday, December 15, 2005

Sensuality is a delicate game.

There is something about perversion that makes it aesthetically appealing. This glass is made of cat hair.

This glass is made of cat hair. This is part of a series of cups/glasses made of cat hair. They are incredibly attractive, soft and pleasant. Yet, at the same time, they are repulsive. They're unbearably close.

This is part of a series of cups/glasses made of cat hair. They are incredibly attractive, soft and pleasant. Yet, at the same time, they are repulsive. They're unbearably close.

This game of closeness, this flirt with the uncomfortable distance when objects go out-of-focus, is what makes them so powerful.

Of course, they have an artistic predecessor: surrealist's Meret Oppenheim's Object, from 1936.

But this here is a different story. It is far from a heavy surrealist joke. The series, called Drink-me-by, has more to do with the transparence of a look, or the hesitating, ephemeral nature of our feeling-of-the-world. It is still a play with the senses, but it trusts us more as viewers (and as touchers).

The author, Verónica Fernandes, doesn't like the comparison. Object was not an inspiration, and for her, it belongs to a different language, a different way of looking at things. She says: "If we were to put it in cinematographic language, The Object is more like a cartoon, with its forms covered by fur. Drink-me-by is for me more like a film, as its very structure is made from the hair"

The cups differ as much as the cats : There is even one you can actually drink from - or mistreat. It has a fine layer of silicone, giving it new qualities:

There is even one you can actually drink from - or mistreat. It has a fine layer of silicone, giving it new qualities:

I had the great privilege of seeing these objects come to life. Their author has not exhibited them anywhere. She hasn't even thought about it - but if you know of a gallery that would be interested, please let me know. They definitely deserve to be seen outside of this modest virtual setting.

(all pictures of Drink-me-by are by José Miguel Soares)

Labels: sculpture

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Michael Hutter is a painter, a visual artist in the classical meaning of the word. Some of his pieces seem combinations of Dali and Beksiński. Others are closer to sci-fi yet others seem games with painting conventions. Take his The Girl and Death (2005), echoing as if in a crazy mirror the romantic works of the likes of Munch or Schiele. This time, though, sexuality is present in a different, contemporary and self-ironic way:

And then, there are his erotic engravings, full of tension and strange perversions. Even the most innocently sexual scenes take place in somewhat creepy settings. The idyllic stories have dark backgrounds, as if innocence, here, was just a cover-up, a play-on-words.

(via)

Labels: painting/photo

Poetry on the internet is a delicate matter. More: poems are a delicate matter. They are fragile, require faith.

And the internet doesn't seem to have the required stillness that reading a poem might demand. But it has other advantages. And Born Magazine uses them, combining flash animation with poetry and music, turning poetry reading into a truly aesthetic experience, that is, speaking to the senses.

My problem with some of the works, as with Courtney Queeney's Origami, is that it could very easily be considered kitsch. And the problem is not with the poem, nor is it actually in the flash animation. It seems to be the combination of the two, which turns a pretty poem and a pretty animation into an all-too-sweet experience. Too much sugar. But then, not all works are like that. Many are darker, more aggressive. Some are gloomy. But in all cases it seems the flash-maker really creates the poem. This goes further than classical "interpretation" of a play. The direct impact of sight and sound appears as much more potent than the subtile work of a poem. I need to digest a poem in order for it to have impact. But by the time I finish watching the animation, the story is over, my wave of emotions (or wavelet, in case of weaker works) has long gone, and there is no turning back. In some works you can stop and decide when to read, but the graphical side seems to take over.

But then, not all works are like that. Many are darker, more aggressive. Some are gloomy. But in all cases it seems the flash-maker really creates the poem. This goes further than classical "interpretation" of a play. The direct impact of sight and sound appears as much more potent than the subtile work of a poem. I need to digest a poem in order for it to have impact. But by the time I finish watching the animation, the story is over, my wave of emotions (or wavelet, in case of weaker works) has long gone, and there is no turning back. In some works you can stop and decide when to read, but the graphical side seems to take over.

But then, maybe that's the trick? I wouldn't go to a poetry page anyway, and here I am trying to go back to the poem to discover it without the all-too-clever animation. Paradox? Reverse psychology?

Labels: digital

Monday, December 12, 2005

220, F-Space, October 9, 1971: The Gallery was flooded with 12 inches of water. Three other people and I waded through the water and climbed onto 14 foot ladders, one ladder per person. After everyone was positioned, I dropped a 220 electric line into water. The piece lasted from midnight until dawn, about six hours. There was no audience except for the participants.

The piece was an experiment in what would happen. It was a kind of artificial "men in a life raft" situation. The thing I was attempting to set up was a hyped-up situation with high danger which would keep them awake, confessing, and talking, but it didn't, really. After about two-an-a-half hours everybody got really sleepy. They would kind of lean on their ladders by hooking their arms around, and go to sleep. It was surprising that anyone could sleep, but we all did intermittently. There was a circuit breaker outside the building and my wife came in at 6:00 in the morning and turned it off and opened the door. I think everyone enjoyed it in a weird sort of way. I think they had some of the feelings that I had had, you know? They felt kind of elated, like they had really done something.

- Chris Burden

quote from:

Labels: performing

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Photo by Francine Gagnon.

Does anyone say he is his body, period?

What is it that makes the body such a scandal? Is it because bodies we see are not our bodies? Is it this un-identity, the fact that empathy seems like a childish dream, some sort of ridiculous belief? Is it that touching is losing my own touch? Listen to Wittgenstein: The truth is: it makes sense to say about other people that they doubt whether I am in pain; but not to say it about myself.

So there is a basic egocentrism in our thinking about the body. In English, we say "take a walk in my shoes". Compare it to the Polish version: "put yourself into my skin". (Strange, how my skin seems to define me.) Is a racer without his car still a racer?

And that's where the fear of skin appears. And the obsession of skin. Its shapes, tones, actions.

How many skins can I have, how distant is this skin from mine, what can be done with this skin. Using it to re-create identity, as a toy, a scandal, or any other pretext. And we all do it - which is scary, and nice : feel the carress. It translates the other into what's yours.

And vice versa.

NB: Here is a short overview of body in contemporary art (in French)

Labels: controversial, painting/photo

Monday, December 5, 2005

Labels: painting/photo, vvoi's

Mousonturm is organizing an artistic residency for its Plateaux Festival:

Plateaux is a supportive model for young performing artists.

Plateaux invites international artists, performers and companies in the field of experimental theatre, performance art and live art to send in conceptual proposals. The proposals should display a discrete and textually well founded aesthetic position.

Plateaux commissions a limited number of productions and invites the artists for production residencies. The artists can carry out their respective projects at Künstlerhaus MOUSONTURM in Frankfurt/Main or at one of the co-producing institutions. The productions will then be presented at the Künstlerhaus MOUSONTURM during the Plateaux festival in October 2006.

Plateaux deadline

JANUARY 14 2006 (Postmark)

Labels: etc, performing

Sunday, December 4, 2005

Chicken Knickers (1997)

"I was quite a tomboy when I was growing up, I liked hanging out with a lot of boys, and I sort of got used to their way of talking about sex. And at the same time as thinking it was funny, I suppose I was a bit aware that it also applied to

me, and I've always had those two attitudes."We Do it With Love

"I don't think I have a problem with having more than one view about it at once."The Stinker (2003)

Got a Salmon on (Prawn) (1994)

Recently you could buy it at Artangel for under 20 000€...

The Kiss (2003)

"I first started smoking when I was nine. And I first started trying to make something out of cigarettes because I like to use relevant kind of materials. I've got these cigarettes around so why not use them. There is this obsessive activity of me sticking all these cigarettes on the sculptures, and obsessive activity could be viewed as a form of masturbation."

Christ You Know it Ain't Easy (2003)

(link to anarticle about the exhibition here)Beer Can Penis (1999)

Labels: controversial, sculpture

Friday, December 2, 2005

The Polish events, which just keep getting worse and worse, are an inspiration to write about body art and every possible controversial art form I can think of. For now, enjoy some pictures of Paul McCarthy's work:

Here's a free translation of a (fragment of a) recent post about McCarthy's last London show by my friend LunettesRouges:

In a huge abandoned warehouse, models of pirate ships and a few remains of the filming, some heads, arms, swords. This is where Paul McCarthy and his son Damon spent a month filming pirate scenes that are now projected on two sets of screens. It is grotesque, hilarious, carnavalesque, obscene, unsettling, funny, terrifying, violent, perverted, orgiastic, gore, gargantuan. The music is obsessive, deafening. The actors scream, shout, laugh, fight. It's Hollywood and Disney gone amok, perverted, parodied. The pirates attack a village, they kill, rape, torture the prisonners (Abu Ghraib, of course), they sell the girls at auctions. The blood is naturally ketchup, the cut off members are naturally made of plastic, and nothing is done to hide the cameramen or the dummies.(all this off-site from the Whitechapel Gallery)

It's a deformed reality, a repulsive attraction, and, if you don't leave disgusted after five minutes, it's a mind-twisting experience.

And here's an article from the Guardian, in case you want to know more about the man.

Oh, and since it's the right season. Here's a holiday picture, courtesy the very special mind of Paul McCarthy:

More:

Labels: controversial, performing, sculpture